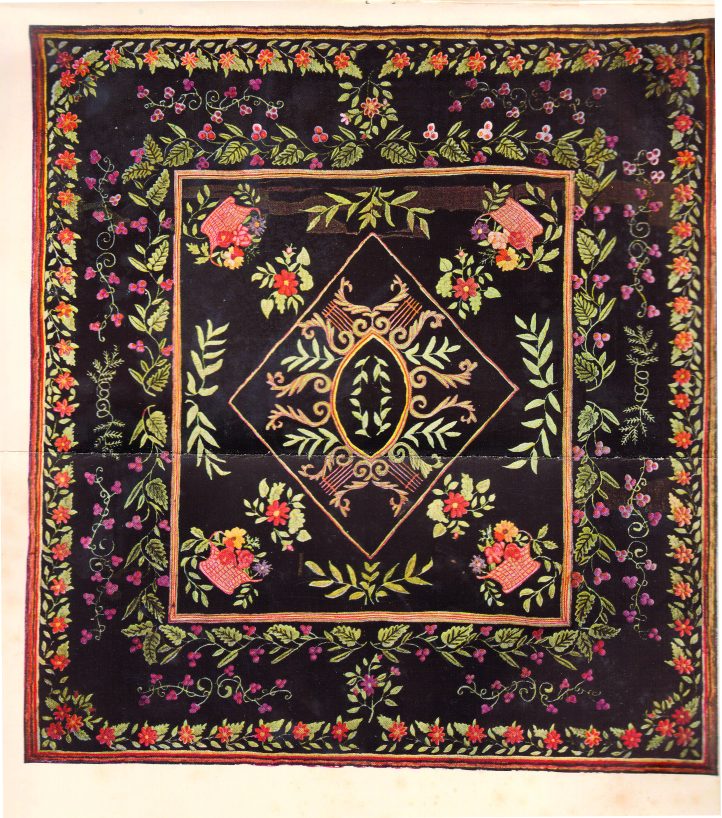

This rug was sold in 1923 at the Shoemaker auction. The rug had an intriguing story: because of its size, a special loom was set up to weave the burlap foundation (the rug measured 14′ x 15′) and more than three dozen Massachusetts women hooked it. The rug sold for $2,000 in 1923, approximately $25,000 today. The flaw in the image above is because this is a photo of a photo; the previous photo is creased.

With the 20th century on the horizon, Americans were prepared to celebrate their history as well as their future. The past had become the place to be, and decorators and designers turned to the 17th and 18th centuries, copied the furniture and textiles, and called the new “old style” the Colonial Revival. “‘Colonial handicrafts’ is what they call it,” said one newspaper writer, “though it might better be named ‘pioneer mothers’ handicrafts. Wherever the strong, fine women of the early days in this land settled . . . these women spun and wove and dyed and knitted and braided . . . The pioneer mothers did this work because they had to and ornamented it because they wanted to.” Interest in hooked rugs soared and among the collectors were society women who turned to well-known antiques dealers for decorating guidance.

One of the earliest tastemakers to promote the art and old hooked rugs was James M. Shoemaker, owner of a rug manufacturing company that made reproductions of Persian rugs. Shoemaker was a savvy businessman with an excellent eye for design and a sense of knowing what the public was about to want. In the early years of the 20th century, he traveled throughout New England and the Canadian Maritime regions, stopping at farmhouses or shops to inquire about antiques. Along the way, he saw hooked rugs and was immediately smitten by the “handsomest and finest specimens of this domestic art and ingenuity of the American housewife.” Shoemaker claimed that he found one of the loveliest rugs thrown over a sailor’s old sea chest and described his find: “Made by a sailor in the idle hours of a long voyage . . . the heart in one corner, the anchor in another and a star in the center were all symbolic of the maker’s thoughts and aspirations. The colors are red, lavender, sapphire-blue and tan.”

Shoemaker purchased more than 600 hooked rugs and soon he took 300 rugs to an exclusive New York City shop. The store manager agreed to take the rugs on consignment, but he thought the rugs were little more than curiosities. Imagine his—and Mr. Shoemaker’s—surprise when the stock sold out in a few days. Word of the hooked rugs spread quickly through Manhattan society, and the collecting craze was on!

In May 1923, the Anderson Galleries of New York sold the rest of the Shoemaker collection at a well-publicized auction, which also became a social event for the wealthy who flocked to buy these new collectibles. The public was somewhat familiar with hooked rugs, especially people who grew up in or nearby New England, but the early rugs had nearly always been treated as utilitarian or decorative and certainly not elevated to the realm of “art.” But when set in fine auction houses and featured in newspapers, the rugs underwent a change and were viewed with new eyes and described in detail.

The Shoemaker sale offered buyers a broad range of rug designs and colors for purchase: a mother cat and kittens on a “red ground surrounded by a lighter one set with flowers,” a rose, a white and black horse vaulting lightly over two rabbits, a panting lion in buff on blue back-ground, a clipper ship with “Welcome” sailing along the rug, a parrot sitting on a branch of a tree, ducks, a King Charles spaniel “lying on a checkered carpet,” a green and orange dog, a quaint basket filled with roses, a rug with a rooster and bird tracks around the border, a grouping of cats, owls, fish, and a horse near a water pump and tub, and what Shoemaker called “brick house” rugs, which depicted buildings. (These are usually the most expensive rugs when found today.)

Mr. Shoemaker told interviewers that “oft times the elaborate care and time expended on hook rugs made them very precious in the eyes of their owner. These were used only on festal occasions, and then resigned to chests when not on the floor. Rugs reinforced with cotton backing, grown yellow with age, were still brilliant in color. . . . I must say, however, that the rugs that have the most beautiful color appeal are those that not only have continually seen the light but those that have had fair usage. . . . Only the exposure to light brought about the lovely pastel shadings so often seen in the early specimens.”

The Shoemaker auction made hooked rugs among the most eagerly sought-after symbols of the Colonial Revival, and soon other auction houses capitalized on the new popularity of hooked rugs. The most avid buyers were often wealthy society women, who paid prices ranging from a few dollars to a few thousand, a true fortune in the days before income tax. Not long after the Shoemaker auction, Mrs. Edward O. Schernikow of New York City sold her rugs through The Anderson Galleries at sales in 1924, 1928, and 1929. A wealthy widow with ample means to collect rugs, Schernikow owned many fine and rare examples, described in the catalog as the “Work of New England home weavers . . . replete with strangely colored pictures.” (The writer had little understanding about how the rugs were made.)

Still, the designs were described in detail for readers and buyers: “This sale includes the original ideas of the home rug makers. An unusual Maine rug has trefoils and circles of black with rose cen-ters appliquéd to a hooked background of deep rose, with a border of old green. . . . A Maine pictorial rug shows a red cow standing under a full moon before a barn of totally inadequate size. . . . A red-eyed blackbird is perched on a branch in a blue field, surrounded by green leaves and large yellow flowers.” The rugs were called “lovely,” “little,” “charming,” and one writer even commented, “It is surprising how the old-time hook rug workers managed to get character into their designs.” (Not so surprising to a rug hooker!)

The heyday of rug auctions spanned the 1920s and ’30s. The Fred W. Ayres collection sold at the beginning of the Great Depression for the then-enormous sum of $24,000. Many of his rugs were described as colorful florals of greens, roses, browns, ivory, and “brilliant hues,” along with a rare pictorial rug dated 1828 and showing a church flanked by a house on either side with walking figures and gold and blue initials. (Whatever the date meant remains a mystery.) One hooked rug measured nearly 12′ x 10½’. At the Cyrus K. Budd auction, a 12′ x 13′ hooked rug “said to be the largest specimen in existence of its quality and design” was sold to Mrs. L. Havemeyer, whose Sutton Place home was the epitome of wealth, luxury, and style.

The interest in the rugs varied with the designs and colors: while Mrs. Havemeyer swooned over a finely hooked floral, other collectors appeared to be more interested in the rug hookers and their craft. One rug catalog noted, “You need a long memory and a homespun past to recreate the atmosphere of the hooked rug. Making them was self-expression. The excitement of art was there when Winter came, and the peppers hung from the rafters of the farmhouses, and the corn and apples were dried.” The writer went on to imagine the personal connection between the rug and the rug hooker, “There’s your Uncle ’Lisha’s work pants in the lion; dretful stuff to handle, but I think it’s kinda purty.”

One thing in common among all the auctions was the catalog. Old auction catalogs help us sort out hooked rug history and understand the personal tastes of rug makers and rug collectors. Catalog rugs were described in detail, including “the animal patterns, the family cat and dog in attitudes of repose, the wild beast of the jungle, swollen with passion, purple saddle horses running free in conventional landscapes.” The writer called the rugs “primitive,” but admired them for outlasting the aesthetics of the Hudson River School, the Impressionists and the Modernists—a compliment indeed. Other catalogers were less than enthusiastic, calling certain rugs “rare and significant” but noting that the examples were “treasurable but entirely hideous.”

Descriptions in sales catalogs were not always flattering, but they were often precise in their detail. The words described elements, colors, and techniques—and they were often written by auctioneers who may not have had a great appreciation for what they termed “primitive” and “hideous.”

After the rug auctions, hooked rugs were changed forever. The East and Maritime regions were virtually stripped of early rugs. If any good came from this, it was that hooked rugs were distributed beyond New England, and into the Midwest and the South where they inspired artists to take up the hook and fabric and create their own examples. But modern collectors now have to guess at whether a rug was made in the Midwest or brought there from somewhere else. (Apparently, attempts were made to repatriate rugs: one auction catalog and receipt from a Midwest sale in the 1930s indicated that a buyer from Maine purchased a dozen rugs—all listed as Maine made!)

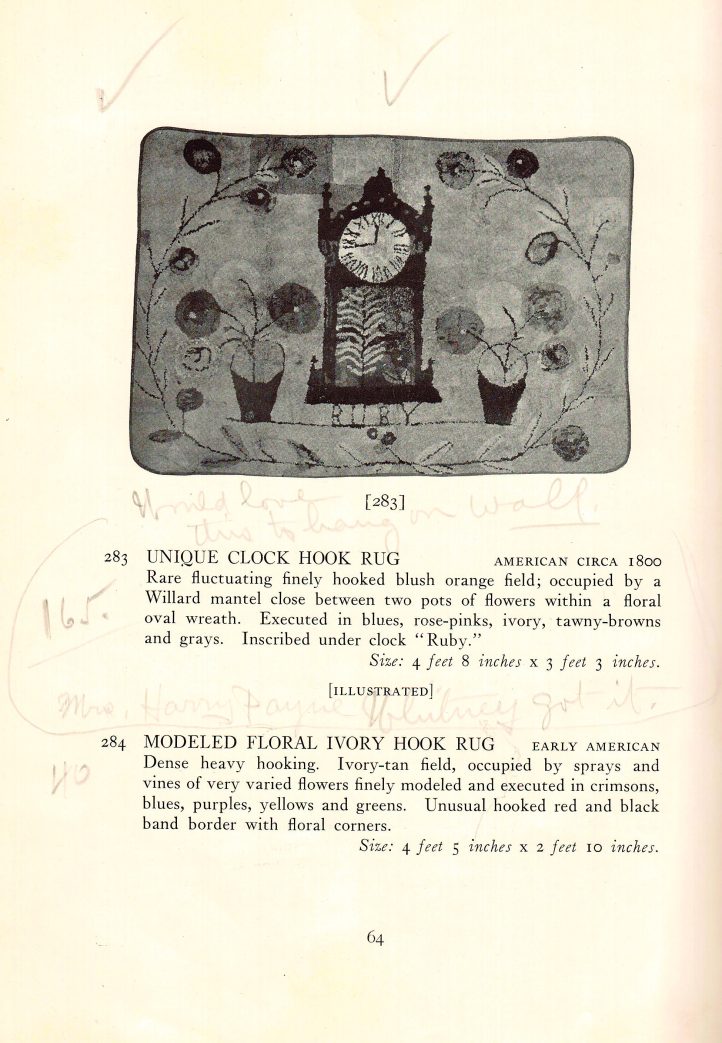

Today’s rug hookers who read old catalogs will discover black and white photos and descriptions reflecting the tastes of the collector and auction house. Some catalogs offer detailed color descriptions, using descriptive words such as jaspé, which refers to shadings and streaks. Even if we cannot see the rug, we can glean information, as in this catalog entry from the 1920s: “Floral Tiger Skin Hook Rug – Golden-tan field; marked with black simulating an animal’s pelt; occupied by a diamond medallion bearing blue lilies and enclosing bouquet of crimson flowers.”

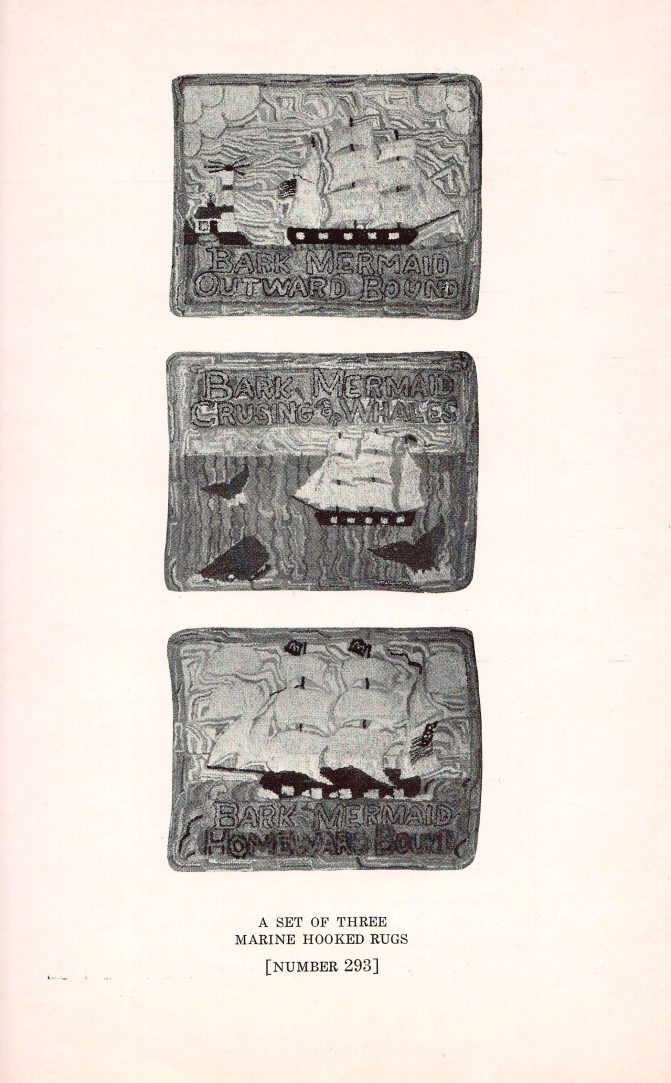

Even in black and white, the pages of a sales catalog can tell us valuable information about the history of rug hooking and the preferences of the artists who created these early rugs.

There were rugs with Waldoboro contouring and sculpting; motto rugs that proclaimed “good luck,” “call again,” “rough weather,” “take a chair,” “be of good cheer,” and other sayings; marine rugs depicting sailing ships outbound, whale fishing and returning to port; mosaic, hit or miss, and many, many “floral sprays.” Every now and then an unusual motif pops up in the description: a sheep framed by flowers and an arched bridge (shades of the British countryside), a lion surrounded by palm trees and patriotic U.S. shields, a compass rose with swirling borders (more quilt than rug.)

It is impossible to know whether colors had faded or reflected those chosen by the artist. Still, the breadth of colors listed in catalogs was as great as any found in a painter’s studio: fawn, rusty black, old rose, magenta, bright blue, orange, rosy black, old red, primrose yellow, mauve, olive, moss, bold rose, old ivory, old white, wisteria, purple, sky blue, sapphire, mulberry, tortoise shell black, and more.

The rug motifs listed in catalogs offer a closer look into the lives of the people who made the art. Mrs. Schernikow owned rugs that would be unusual today, even with the many new designs. Among her collections were a floral rug with ears of corn as the border instead of scrolls; a clipper ship surrounded by whales; a ship near a horn of plenty and the word “success”; and a “rose, white and black horse vault[ing] lightly over two rabbits.” The Shoemaker sale offered a rare rug with a Willard mantel clock surrounded by pots of flowers; a flag with 16 stars on the blue field and 13 stars in the background; crimson birds surrounded by six baskets filled with “colored leafage” and a church and schoolhouse in a winter landscape.

The great rug auctions ended by World War II: with fewer rugs to collect, fewer large collections could bloom. Prices rose for individual items, and continue to do so. But nearly a century after the auctions, mysteries remain underfoot. What became of many of these rugs? Whose floors did they grace, and how many of them remain to be rediscovered yet again, only this time a thousand miles or more from their homes?

We will never know all the answers, but we can still read the old catalogs and imagine a crowded auction house, our raised number and the wonderful sound of “Sold!”