West Virginia State Museum, Charleston, WV Legacy of Craftsmanship Room. WV Division of Culture and History, Stephen C. Brightwell, photographer.

Five years ago I ran across the McDonald sisters of Gilmer County, West Virginia, while visiting the State Museum in Charleston. Actually it was their 5′ x 3′ “tapestry” with hooked border that caught my attention.

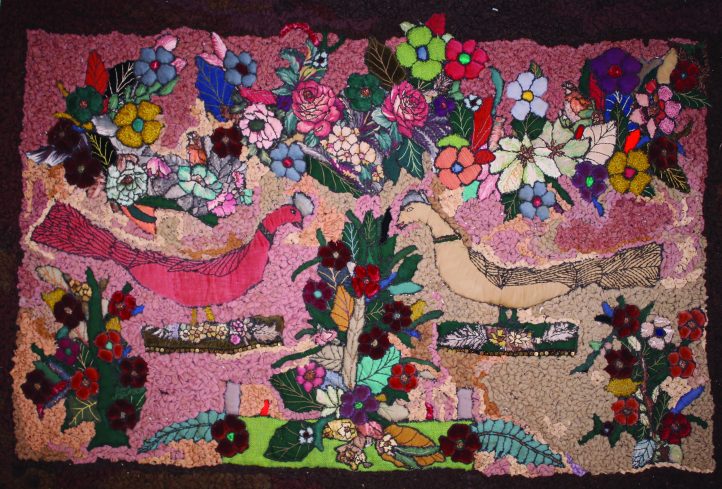

Blanche and Otha McDonald at home with work in progress of “largest” rug including birds. GLENVILLE STATE COLLEGE

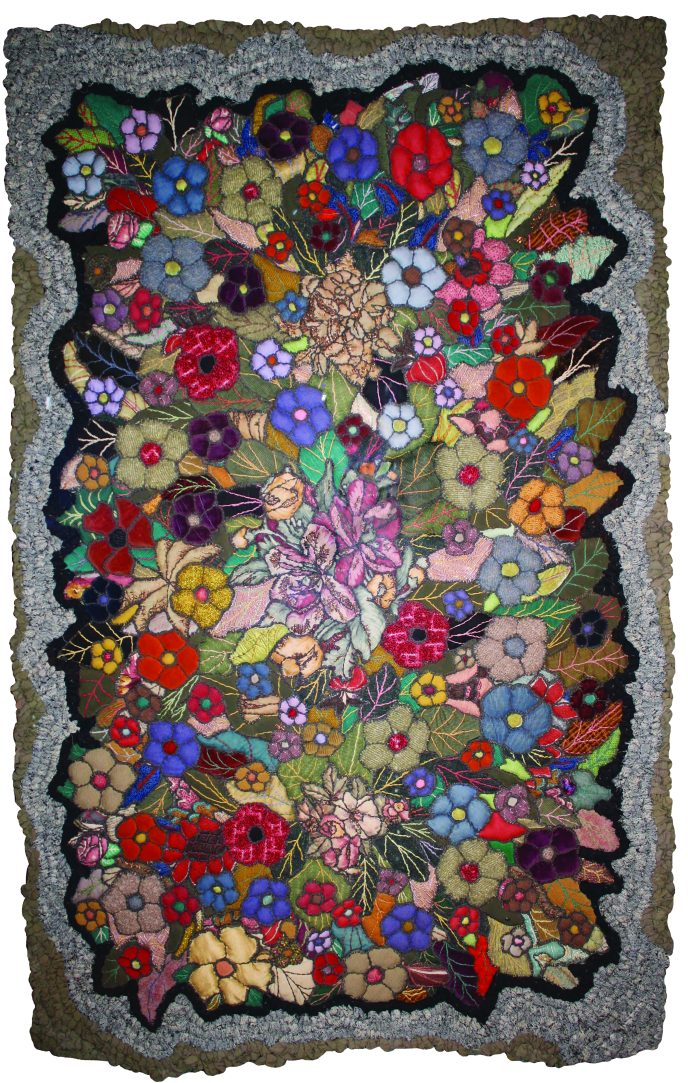

It was prominently hanging in the Legacy of Craftsmanship room next to a patchwork skirt made by the Mountain Artisans. The label reads, in part:

Old Skills, New Markets . . . Arts-and-crafts festivals have created another market for West Virginia artisans, craftspeople, and musicians. This hooked rug, made by Otha and Blanche McDonald of Gilmer County, was purchased in 1970 at the West Virginia State Folk Festival, the state’s longest-running folk festival.

I am sure you can imagine the excitement, thrill, and pride of finding an example of rug hooking displayed next to quilting in a museum.

I had to know more. Who were the McDonald sisters? The rug was made in 1970; could they still be alive? Why did they incorporate trapunto, crewel work, and hooking in their piece? What do their other works look like?

Rug by the McDonald sisters on display in the West Virginia State Museum, Gilmer County, West Virginia, 1970. Approximately 60″ x 36″, mixed media, hand-stitched. SUSAN L. FELLER

I talked with the head curator, who suggested the explosive composition of flowers may have been influenced by English china brought over by their Scottish ancestors. He had no other information about the piece, the women, or their techniques. The State Archives provided their birthdates and parents’ names in Gilmer County . . . and that was all.

Otha McDonald was born September 2, 1892, and Blanche McDonald was born September 7, 1895; their parents were Minnie Furr and John A. McDonald. With that information, I was pretty sure they had passed by now. Their work would have to speak for them.

Maybe I could find some collectors and articles. The leads I took from the display were the West Virginia State Folk Festival and Gilmer County. On the Internet, I found the festival is held in Glenville, WV, and the papers and records from its originator, Fern Rollyson, are stored in the Glenville State College Robert F. Kidd Library Archives. This has been, to date, my best connection for information. The head librarian, Ginny Yeager, and archivist, Jason Gum, provided personal references to the cemetery, family home, a great-nephew, published articles, black-and-white photos of the sisters, and connections to collectors of their work (purchased 50 years ago).

Rug created by Blanche McDonald, 1968 purchase award ($100) by WV Arts and Humanities Council, in archives of State Museum, Charleston, West Virginia. Approximately 36″ x 24″,

mixed media, hand-stitched. SUSAN L. FELLER

Since Glenville and Letter Gap (their home post office) are four hours by car from my home and Charleston another hour farther, scheduling trips to investigate the material took time and money. Each year when I taught at Cedar Lakes, in Ripley, I would coordinate an overnight trip to these areas to ask questions and gather answers, which brought up even more questions.

In 2013, a Tamarack Foundation Fellowship award allowed me to continue research on the McDonald sisters. This award helped me travel around the state, exhibit their story during Rug Hooking Week at Sauder Village in 2016, develop a workshop featuring their techniques, and with this article, fulfill my goal of publishing their story.

Unique design by McDonald sisters with birds, flowers, and filled space; “faux hooked.” Private collection 48″ x 72″ mixed media, hand-stitched. SUSAN L. FELLER

I found an article about a rug by Blanche that received a purchase award from the West Virginia Arts and Humanities Council during the 1968 Appalachian Corridors Exhibition in Charleston. The co-coordinator of the exhibition was Ellie Schaul, an artist still living in the Charleston area. I contacted her about the exhibit, and she told me that she owned a footstool by Blanche! On a visit, I photographed her piece and a painting she had incorporated it into and discussed the upcoming 50th anniversary of that first exhibition in 2018. Her information about the sisters was not from direct contact. But she had a lead: she suggested that I contact the husband of Florette Angel, the crafts representative of the West Virginia Department of Commerce (established in 1964 by the Economic Opportunity Act signed by President Johnson). They had owned a couple of pieces, one shown in The Mountain Artisans Quilting Book by Alfred Allan Lewis, but sold them by 2014. Mr. Angel did not know the sisters personally either, telling me Florette’s job and passion through the 1960s was to travel the mountains and hollows searching for artisans work to represent in national markets. He gave me the catalogs of all three biennial exhibitions and a published review with Blanche’s rug in print.

Closeup of bird rug showing materials, including copper strands from Brillo pad threads. SUSAN L. FELLER

Mrs. Schaul also suggested I contact Donald Page, who was the Director of the Department of Commerce and deeply involved with the festivals and artisans. We emailed, but illness prevented a visit. When I heard of his death, I waited several months to contact Mrs. Page to see “the largest rug the sisters made.” In our phone conversation, she described the rug as having two large birds; one of the archive photos from Glenville State College features the ladies holding a very large rug in progress with birds, flowers, and the patterned backing fabric evident. I told her of this photo, and we were excited to meet. My visit to see the rug, to examine and photograph it, is a memorable highlight of my search.

Back of purchase award rug, archived at State Museum, Charleston, West Virginia. This photo shows the handwork of random stitching, attaching all materials seen on the front. SUSAN L. FELLER

I learned that the McDonalds worked with 1960s garment and drapery fabrics: velvet, corduroy, brocade, chintz, wool, and knits were used for the decorative motifs. Yarns of wool, threads of cotton, and copper (untangled from Brillo pads) were sewn connecting the elements and adding details, such as veins and flower centers. The backing material was a close weave, not as open as the linen or monk’s cloth used by rug hookers today. I could see in the photo of Mrs. Page’s incomplete bird rug that the backing is a popular printed pattern used for draperies. Looking closely, the backing also shows on top: I realized that it is a flannel with printed airplanes used for pajamas, (also too tight to hook through easily). When I had a chance to look at the back of this piece, I verified that they did not hook the loops, as we presumed from the original label. The loops were hand-stitched to the foundation. The random threads from this stitching show on the back.

Value your work!

Document it for posterity!

Document your process, not only the finished product.

Take photos of materials, tools, and especially photos of you working on a piece.

Describe techniques in articles, posts, and social media comments.

Document how you wereinfluenced, why you selected a subject, topic, or style.

Create an ongoing chronicle of your work, listing size, materials, and where the pieces end up: as gifts, sold, or in your own collection.

Label your work. The McDonald sisters did not.

Designate where you want the documentation to end up: choose a public archive to receive them, perhaps a local historical society, a college library, or your state arts council.

Returning to the State Museum, I examined the award-winning piece mentioned in the Appalachian Corridors Exhibition catalog. It is in the archives and not on display. I was pleased to be able to look at the back and confirm that the same methods were used, with an unprinted, tightly woven backing fabric showing the stitching.

Remember how I said the research led to answers and questions? Why did Blanche and Otha mimic the loops of rug hooking, using a labor-intensive method of hand-sewing each loop? There are no rug hookers listed as participating in the festivals in and around Glenville in the 1960s. These ladies did not drive; they pulled a red wagon three miles from their home to their nephew’s home monthly for supplies and mail. Otherwise, they were self-sufficient, living together on their isolated family farm. They demonstrated annually at the festival, sent work out through the marketing leads Mrs. Angel created, and would have met visitors from out-of-state only at those times.

From conversations with collectors and articles I gleaned, their needlework style was uniquely their own. Perhaps their Scottish mother taught them to stitch this way, just as I learned crewel and embroidery from my grandmother. Trapunto quilts are still made in central West Virginia today. But the rug hooking skill is not common.

I consulted with Jan Whitlock, author of Hand Sewn American Rugs and Jessie Turbayne, an authority on hooked rugs, for known examples of “faux hooking.” Our best supposition is that they subscribed to women’s magazines which showed rug hooking, and they liked how it looked and adapted it to the stitching and materials they had on hand. They had the time, and worked on large and small pieces, producing piles of rugs, wall hangings, and footstools.

I am five years into this journey. Along the way I have learned a few points to share with my contemporaries working in the fiber arts. Most important: document your finished pieces AND your process. The McDonald sisters did not, and thus the mystery surrounding their rugs.

Otha and Blanche have only been gone since 1975 and 1976, yet the story of the “who, what, where, when, and how” of their wonderful work is as elusive as if they had died in 1875.