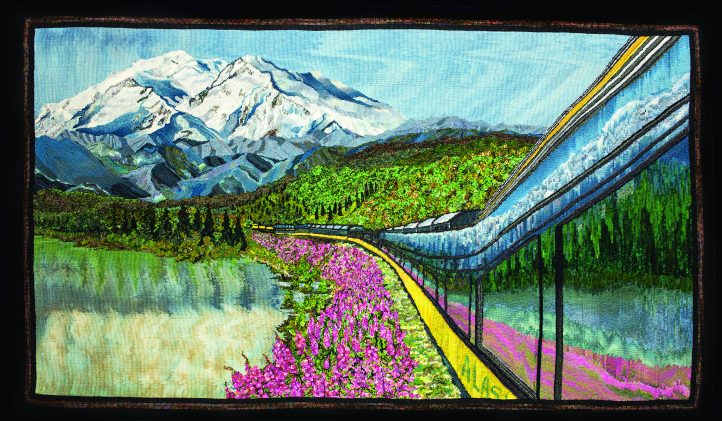

This Train, 80″ x 47″, hand-dyed wool on linen. Designed and hooked by Jen Lavoie, Huntington, Vermont, 2012.

BY PAULETTE HACKMAN / PHOTOGRAPHY BY ANNE-MARIE LITTENBERG

Hooking artist Jen Lavoie has reaped many wonderful rewards for her art rugs—original pictorials showcasing tour-de-force technique and gorgeous high-key, hand-dyed color applied to stunning compositions ranging from landscape to narrative to portraiture. To the experienced viewer, Jen’s rugs are easy to spot and in a class by themselves. Usually ambitious in size and subject, realistic to the smallest detail, dramatic in the play of light and shadow, her hooked art—wool paintings—elicit ohs and ahs and wows and How does she do that?

Since the late nineties when the Huntington, Vermont, artist started exhibiting her work at Hooked in the Mountains, the popular hooked rug expo in Burlington, Vermont, Jen’s rugs have consistently made Viewers’ Choice, an honor bestowed by visitors who select three favorites among some 600 or more rugs in the show.

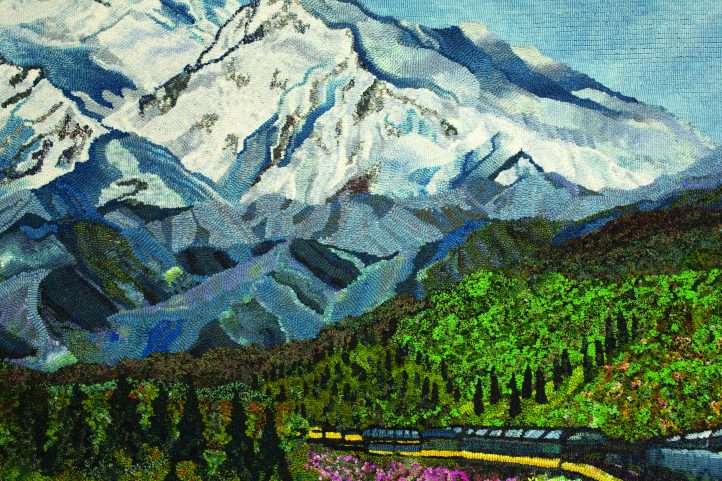

At the most recent show, 2012, This Train was also honored by the Shelburne Museum Award. According to the judges, “Jen Lavoie’s This Train is such a knockout. The scene, scale and perspective, the way the lake and mountains reflect off of the train . . . awesome!”

But for Jen Lavoie rewards of a different sort trump public admiration. As with many artists, reward comes from the work itself, embedded in the practice of craft and the process of discovering a new creation story emerging from each new subject.

With process being key, choosing the right subject is essential, especially considering the long haul of hooking a large rug with the kind of fine detail that often warrants a #3 cut. It has to have major staying power. And it should definitely prompt her curiosity. “It is a real exercise in faith,” Jen says. “I have to love it [the subject]. If I want to do another corn piece, for instance, I have to be prepared to think about corn for the next six months. I’d have to think about the way the leaves turn, about the color. . . . I’ve got to explore it and I’ve got to care enough to learn something more about it.”

It’s also important for the subject to stimulate imagination—hers as well as the viewer’s. “My goal is always to draw you in and make you feel that this has a meaningful story for you,” she explains. “I relate to this because when I was a child I used to do that with pictures.”

The emphasis on viewpoint is common among storytellers from all mediums. Jen will often employ an unusual perspective to add interest to her subject. “The perspective I choose is always [to suggest] that where you’re standing you are a part of that scene,” she says. “That’s my goal. I do it for myself too. I want to feel like I’m there.”

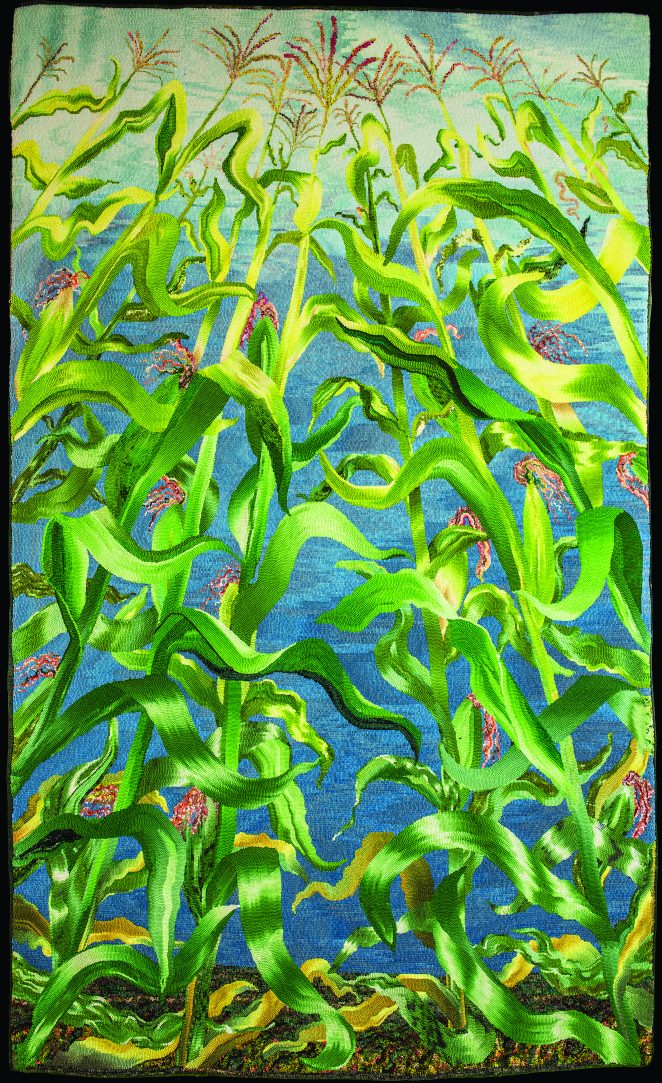

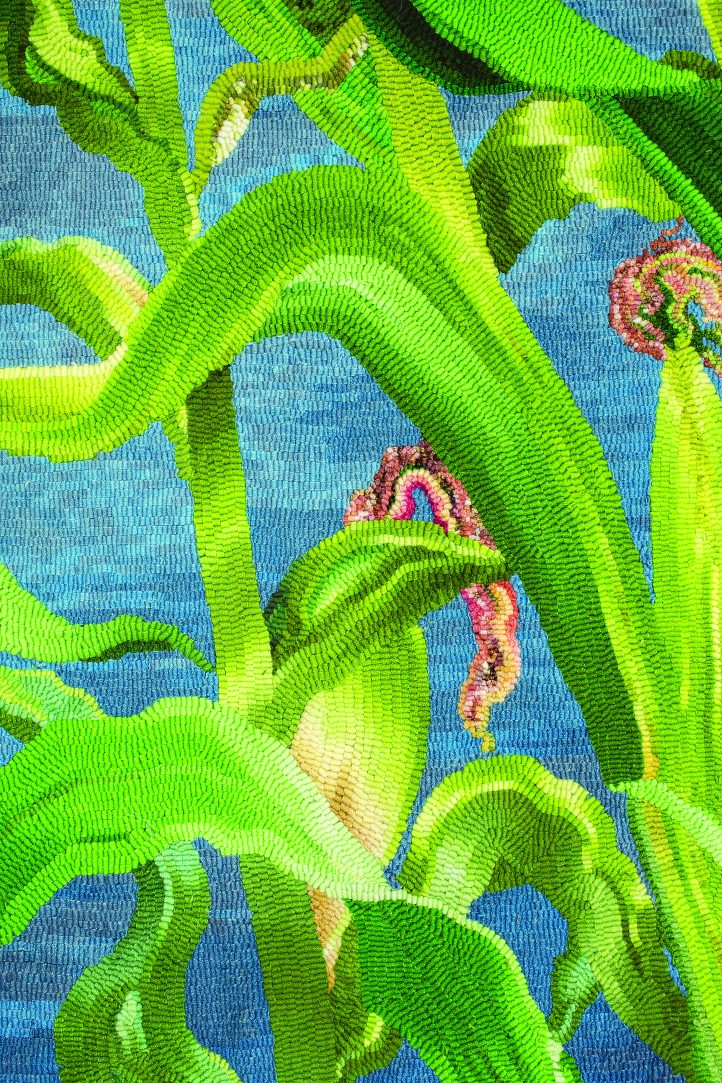

Corn II, 51″ x 85″, #4-, 5-, and 6-cut as-is and hand-dyed wool on linen. Designed and hooked by Jen Lavoie, Huntington, Vermont, 2010. Jen had previously hooked a corn rug, which was then purchased. “After selling ‘Corn I,’” she said, “it was obvious that I was going to miss that piece. So I hooked another for me.” Jen said that when she was growing up and visiting her grandparents in Middletown Springs, Vermont, she spent a lot of time in the cornfields playing with boy cousins. This piece, she said, was about the beauty of looking up into the sunshine. And as a postscript, she added, “I still want to hook another corn piece. I love the freedom of creating any kind of leaf shape that I feel like at any given moment. It is like dancing or choreography when I draw them, and I like to make them flow and wave and do different things. I love that about hooking. I can do anything I want.”

To appreciate the way this works, consider the perspective in Corn, which brings the viewer inside the cornfield, close to the earth, thus adding dramatic tension to what’s basically a static subject. Or with her chosen perspective for Hawaii, the viewer emerges from the jungle at a clearing which might well be a first thrilling view of ocean. This Train positions the viewer careening around a curve with reflections from sky, lake, flowers, and snow . . . bouncing and blurring the boundaries between technology and landscape elements.

Jen’s gorgeous depiction of swaying and bending leaves owes much to an appreciation of movement—going back to her training in dance.

Two themes have contributed to Jen Lavoie’s journey as an artist: the influence of her grandmother’s artistic achievements and her own creative background in dance and drama.

Growing up, Jen knew her grandmother hooked rugs but, like most kids, she viewed activities of the adult world with only a hazy awareness and appreciation.

“After she died and I was older, I started looking harder at what she made,” Jen recalls. “She was designing her own rugs—they were usually gifts for family members—and influenced by the Modern Art of her day, she created Abstracts.”

In 1987 when Jen came into possession of her grandmother’s hooking supplies—a Puritan frame, Rigby cutter, “jars and jars of wools (strips) and old projects,”—she recalls, “I had to figure out how to hook based on my grandmother’s rugs. I couldn’t complete her unfinished rugs, though, because only she knew where she was going with her designs.”

With supplies and tools in hand, Jen taught herself rudimentary hooking skills; her first project, a hooking of her brother’s home, was made as a gift. Showing this to a friend one day, she learned that a whole community of rug hookers existed practically on her doorstep.

“When my friend Polly brought me to my first guild meeting,” she muses, “there were all these women and they were all following ‘Roberts Rules of Order.’ I was amazed. When I showed what I was working on they all said, ‘Ahh.’ I was so thrilled!” She laughs. “I realized later they always said this when they saw someone’s work. It was a very supportive environment.”

Still a believer in the output of other artists in her craft and the importance of a supportive atmosphere, Jen is now in her third year of chairing the Hooked in the Mountains Show, a mammoth undertaking that hangs some 600-plus rugs, welcomes 1,500 visitors, presents a roster of speakers, and hosts numerous workshops over its multi-day run.

Jen’s next big step after joining the guild was to attend rug camp and take a dyeing class with master dyer Ingrid Hieronimis (author of dye book Primary Fusion), thus ushering in her favorite part of the hooking process. “For me,” she says, “dyeing is the thrilling, uncontrollable part of the process. It’s then that a project seems to move toward actual creation.”

As hooking took hold as an important creative release, Jen’s background in drama and dance began to resonate with her artistic sensibility.

“The dancer in me wants things to flow energetically and without strain,” she explains. The act of drawing her design on linen—often working large—presents such an outlet. “In our art form,” she notes, “spontaneity is more about creating an illusion of flow. Because—let’s face it—[with rug hooking] we cannot be spontaneous. So the flow of the piece, for me, is about my Sharpie on linen. That’s where my big body movement comes in.”

Jen’s drama background connects with her goal of staging a story through her hooked composition—for the viewer as well as for her—to discover. “When I approach a new piece I approach it in similar ways to drama,” she says. “Who are the characters in this piece? The leading ladies? The protagonist?”

In a similar vein—though, to most, an unusual comparison—she explains similarities between acting jobs and working on commissions. “You still have to fall in love with the subject,” she notes. “It’s like playing a role in acting. You won’t do a good job with that character until you learn how to really have compassion for that person. What I have to be compassionate about in a commission,” she explains, “is just the process.”

Abundant accomplishments and rewards aside, almost every artist yearns for that one elusive thing. For Jen, it’s those abstracts that came so easy to her grandmother. “I lust after hooking an abstract,” she says. “I’d just love that spontaneity—creating something not so controlled.” But then perhaps she hears herself—the conundrum. “At the same time,” she laughs, “that’s what makes things beautiful—using creativity to control the uncontrollable.”

OUT OF CHAOS COMES ORDER

This is a photo of Jen’s potential colorations of corn leaves—illustrating that certain look of wool chaos which hookers come to trust as “process.” Can you imagine, though, showing this part of the process to a client who has never set eyes on a hooked rug in progress? A client who’s commissioned a hooked rendering of a beloved summer place that exists only in her memory, described only verbally? As Jen tells the story, the client who was called in to view such a customary layout of possible colors (albeit another project) was understandably a bit unsettled. Having seen only a beautiful completed rug, the client knew nothing at all about rug hooking’s magical, transformative process. Yet, the final interpretation, Jen said, was so close that the client wondered if Jen actually had known the very place after all.

HOOKING THIS TRAIN

This Train, 80″ x 47″, hand-dyed wool on linen. Designed and hooked by Jen Lavoie, Huntington, Vermont, 2012.

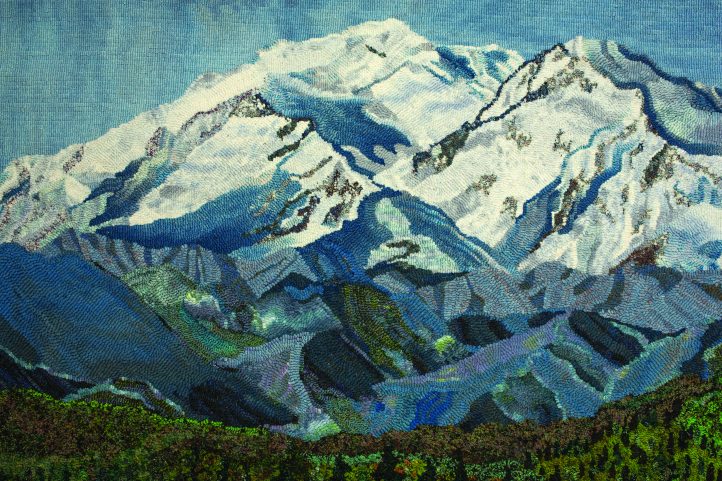

My husband went to Alaska on a business trip. He took many fantastic photos from the train as he was heading to Denali National Park. I needed a project so I decided on an Alaska rug for his great room. I wanted to approach it as a commission piece, as if he were my client. I would focus on meeting his expectations but at the same time bring my own artistic voice to the project. But he already had the great photos and his memories. How could I improve on that?

A frustrating aspect for most visitors to Denali (Mt. McKinley) is that the mountain is so often hidden in the clouds. Jim saw glimpses, but was not able to capture it. I knew I could bring the mountain to him! I also asked myself the question I ask my students: “What three words can describe, in a nutshell, the experience you want for the viewer?” My words (for this piece) were Magnificence, Power, and Beauty. To keep it simple I would stick to the three large-scale elements: the train for Power, the detail of the fireweed for Beauty, and the vast landscape for Magnificence.

“This is the piece that I couldn’t give up on when I wanted to so many times,” says Jen.

Another stunning aspect of Jim’s photos was the reflection in the windows on the train. I thought of leaving it out, because I knew it would be hard to hook! But without it, the train element would just be a solid, violent force. I wanted this train to have a powerful, positive impact. The train’s function is to bring people to the beauty. And thus, the reflection would soften the train and represent the eyes of the people on the train.

For the viewer to feel a sense of majesty, I wanted the point of view to be outside the train, like that of a bird flying alongside. I had the artistic freedom to do that. By changing the angle of the train, the windows now reflected what was not visible in the photo. I no longer had the photo as a guide. I was on my own. I had to imagine what the people inside the train were seeing outside. I tried twice to paint and hook the wool for the train windows but failed miserably. Trying to calculate where each color transition would “pull up” was impossible because of the vanishing point perspective of the train. There were too many elements to try and match. It really was crazy mental gymnastics. I finally resorted to fine shading each specific element for each window section of train.

I started the rug in early 2008, but I didn’t get serious about working on it until 2011. (I almost was thwarted by that window reflection!) With only six months before the Green Mountain Rug Hooking Guild’s 2012 rug show, Hooked in the Mountains (Shelburne, Vermont), I was doubtful if I would finish. Based on my daughter Sydney’s extrapolation of my hooking rate/minute and the amount of empty linen left in the rug, I would have to hook at least seven hours per week in order to finish in time for the show. At first, this seemed quite feasible; however, I know that for one hour of successful hooking on a challenging piece, I need to hook for about six hours, including trips to the dye pot and all those “reverse hooking” (pulling out loops) sessions! Needless to say, it became a full-time job. I hooked at least seven hours per day for six months to finish.

What really kept me at it when I wanted to quit, were the lyrics of Bruce Springsteen’s song, “Land of Hope and Dreams.” My brother Tim died unexpectedly in January at the young age of 53. He was a devoted Christian and I knew that he had boarded that train to the land where “dreams would not be thwarted and faith would be rewarded.” With plenty of time for loop-pulling meditation, I would think of him, riding that train, being one with the wonderful mystery of the universe. Creating This Train renewed my joy and gratitude for all things beautiful and majestic on this earth.

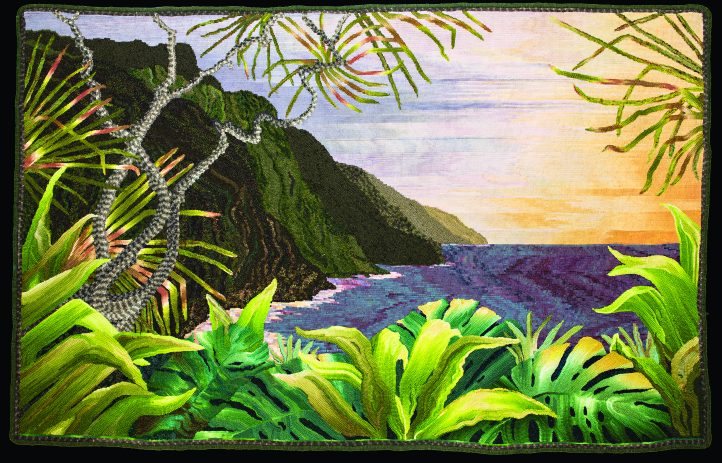

Kauai, 70″ x 46″, #5- and 6-cut as-is and hand-dyed wool on linen. Designed and hooked by Jen Lavoie, Huntington, Vermont, 2011. Able to accompany her husband to the Hawaiian island of Kauai on a business trip, Jen was especially drawn to the spectacular Nepali coast. “On one side of the trail is rainforest—dense, dense rainforest—and on the other side is the ocean,” she said. “The chance to hike the long Kalalau Trail down to the shore was denied to us because of high flowing streams and rain at the time. One fellow traveler was actually trapped on the wrong side of a river and had to spend a long cold night in the forest! We had to be content with short day hikes.” Jen said she had no photos of any particular spot to work from as they never saw sunrise or sunset. “But,” she said, “I did try to approximate the shape of the famous silhouette of the shoreline.” She had also originally planned on flowers but they struck her as “too hokey” and typical. “It was the giant leaves and power of the volcanic cliffs against the shoreline that struck me,” she said, adding, “There is a certain amount of negative space in the ocean but I like it because it makes me think of the whales that were constantly leaping and dancing off the coastline the entire time we were there.”

THE SKY’S THE LIMIT

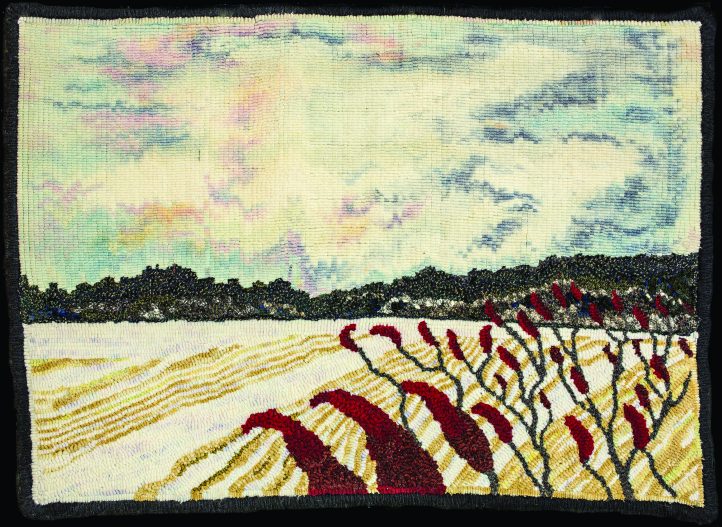

Sumac, 25″ x 18″, #4-, 5-, and 6-cut as-is and hand-dyed wool on linen. Designed and hooked by Jen Lavoie, Huntington, Vermont, 2011. Jen also calls this rug “a little project using up painted skies.” “I had painted a bunch of skies,” Jen says, and hooked this one on linen “without any plan or design for a landscape underneath it.” When she saw it hooked up, she said, she particularly liked the pink, white, and blue pastel effect, so she hooked a familiar field that would have another pastel palette of pale yellow and white. She said, “I see [the field] as I drive into the neighboring town.” The next motif she added was the sumac, a plant she loved because it brought to mind her grandmother’s sumac lemonade. “I am not usually a red, white, and blue fan for color schemes, but I love it here,” she said.

When Jen dyes skies she uses jars of primary colors. “And I mix them as I go in other separate pans.” According to the cut size, she figures four to five times the width she needs. For This Train, for instance, “The sky had to be 24 feet wide—or maybe a little less,” she says, “because the mountain is in the middle of it.”

Sometimes she will then hook the dyed piece straight across, in order, for a particular sky pattern. But she also hooks vertically. “I’ve experimented with hooking skies directionally so that I keep the pieces together, but I flow the direction of the hooking so that you’re getting swirls in the directional hooking but you’re also keeping the colors together,” she explains.

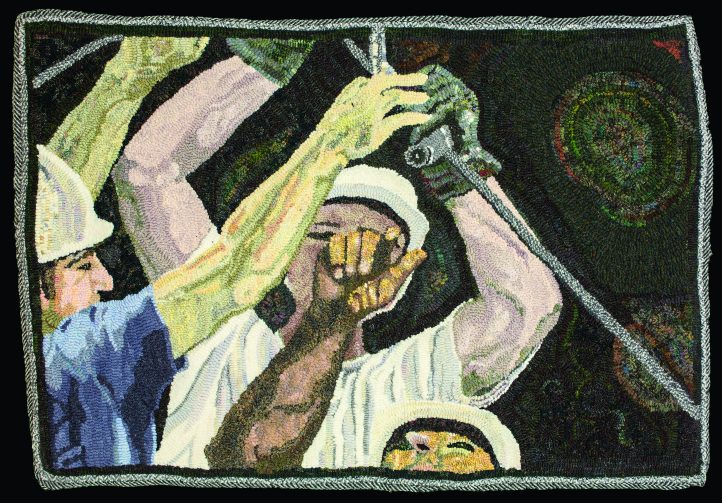

Working, 27″ x 18″, #3-, 4-, and 5-cut as-is and hand-dyed wool on linen. Designed and hooked by Jen Lavoie, Huntington, Vermont, 2011. This design was adapted from a newspaper photo for Hooked in the Mountain’s 2011 theme of “working.” Jen commented, “I liked the perspective of the men with all their hands in the fray. I really like the idea that cooperation on the job is the real meaning of success. When you consider the conditions they often have to work in, linesmen are amazing—unsung heroes in times of crisis.” To zero in on her main interest (the men working), she elected to remove any sense of where they were and made the choice to remove background detail pertaining to where they were working. “The background hooking,” she said, “ends up being just about energy to me. I love that about art: some-thing doesn’t always have to be real. Sometimes it can just be about energy.”